The trail doesn't just take you up a mountain; it takes you into a secret that Northern Tanzania has been whispering for millennia. Beyond the postcard-perfect summit of Kilimanjaro lies a world where the air smells of wild jasmine and ancient moss, where stone-walled villages in the Pare Mountains still follow the rhythms of the moon, and where the "sky islands" of the Usambaras hide creatures found nowhere else on Earth. But...

The Chagga people of Kilimanjaro: Guardians of Land, Culture, and Mountain Life

The morning mist on the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro doesn’t just obscure the view; it holds a secret. As you step into the cool, shaded world of a Kihamba garden, the temperature drops, and the air fills with the scent of damp moss, bruised banana leaves, and the spicy, medicinal whisper of the Ikiingiyi bush. Here, the mountain doesn't feel like a physical challenge to be overcome, but like a living, breathing teacher.

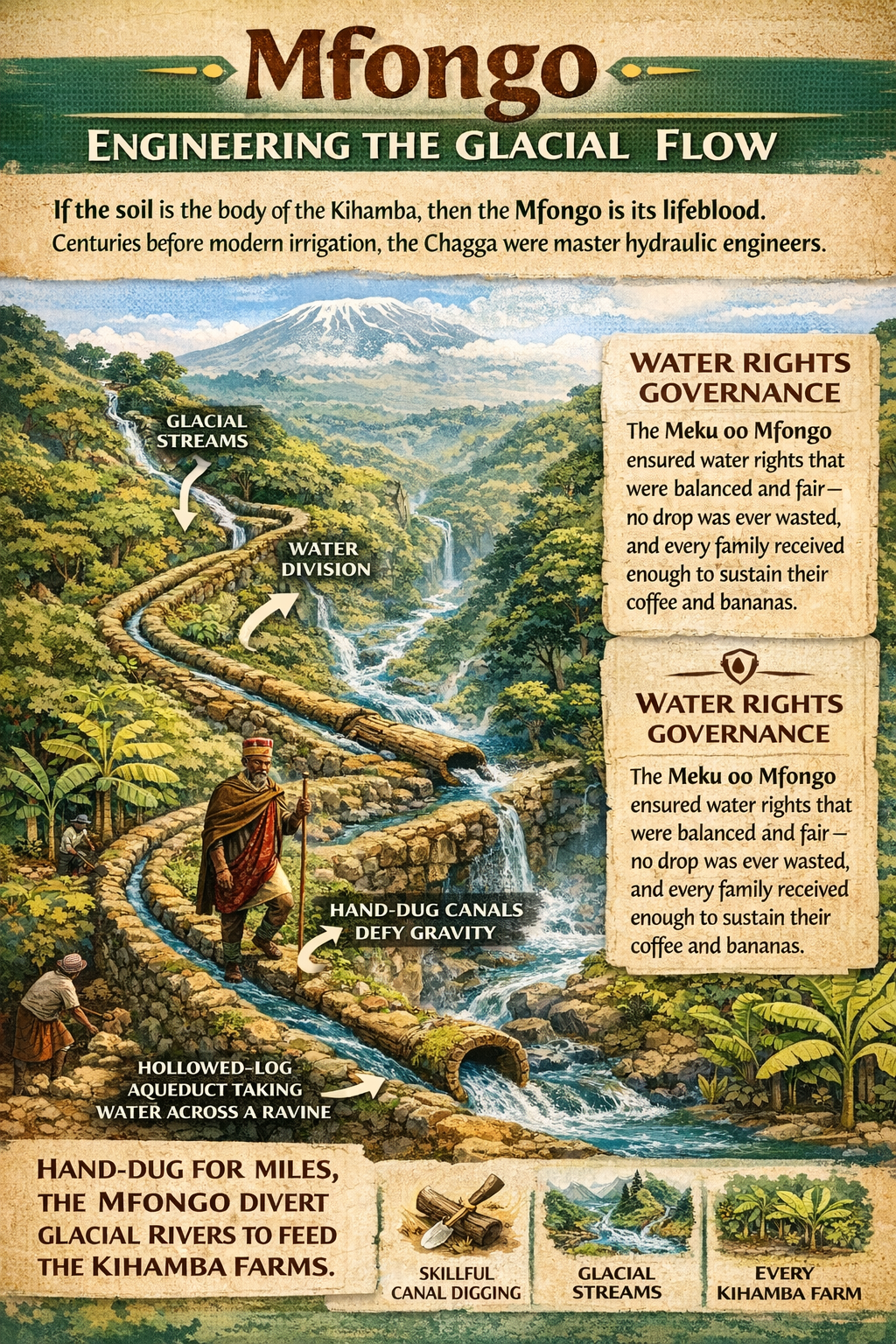

This landscape is a masterclass in harmony that has endured for centuries. Every hand-dug Mfongo canal and every iron tool forged by the village blacksmith tells a story of a people who mastered the art of "Vertical Living" long before the modern world began searching for the meaning of sustainability. Historically, this soil has witnessed a profound evolution—from the absolute authority of the Mangi chiefs to the arrival of the "Iron Snake" railway, which transformed a local harvest into a global heartbeat.

Why does this matter? Because in a world of fast-paced change, the Chagga community offers a rare blueprint for resilience. It is a place where a single Isale leaf still carries the weight of a legal seal, and where the "cooperative spirit" isn't just a business model, but a survival strategy that reclaimed a Nation's destiny.

At Kijani Tours, we believe that the most meaningful journeys aren’t measured in altitude, but in the depth of our connection to the land and its guardians. We invite you to set aside the summit maps for a moment and step into the green cathedral of the mountain. From the first coffee seeds planted in the shadow of Kilema Mission to the ancestral wisdom that still guides the flow of the water, let us explore the enduring legacy of the people who call the "Roof of Africa" home.

1. The Genesis: Of Dwarfs and Ancient Shadows

To understand the Chagga, you must first understand who came before. Long before the Bantu migrations brought the ancestors of the modern-day Chagga to these slopes, the mountain belonged to the Wakonyingo.

Oral traditions describe the Wakonyingo as a legendary race of "mountain dwarfs." These were not mere myths; they were regarded as the original guardians of the high-altitude caves and hidden ravines. They were said to be masters of the mountain’s secrets, possessing the power to hunt down those with "bad intentions" towards the land. While they were eventually absorbed into the growing Chagga clans, their presence is still felt today. When a Kijani guide takes you past a deep volcanic gorge, they aren't just showing you geography—they are showing you a dwelling place of mystery and ancestral power.

2. The Architecture of the (Chagga Homestead) Kihamba

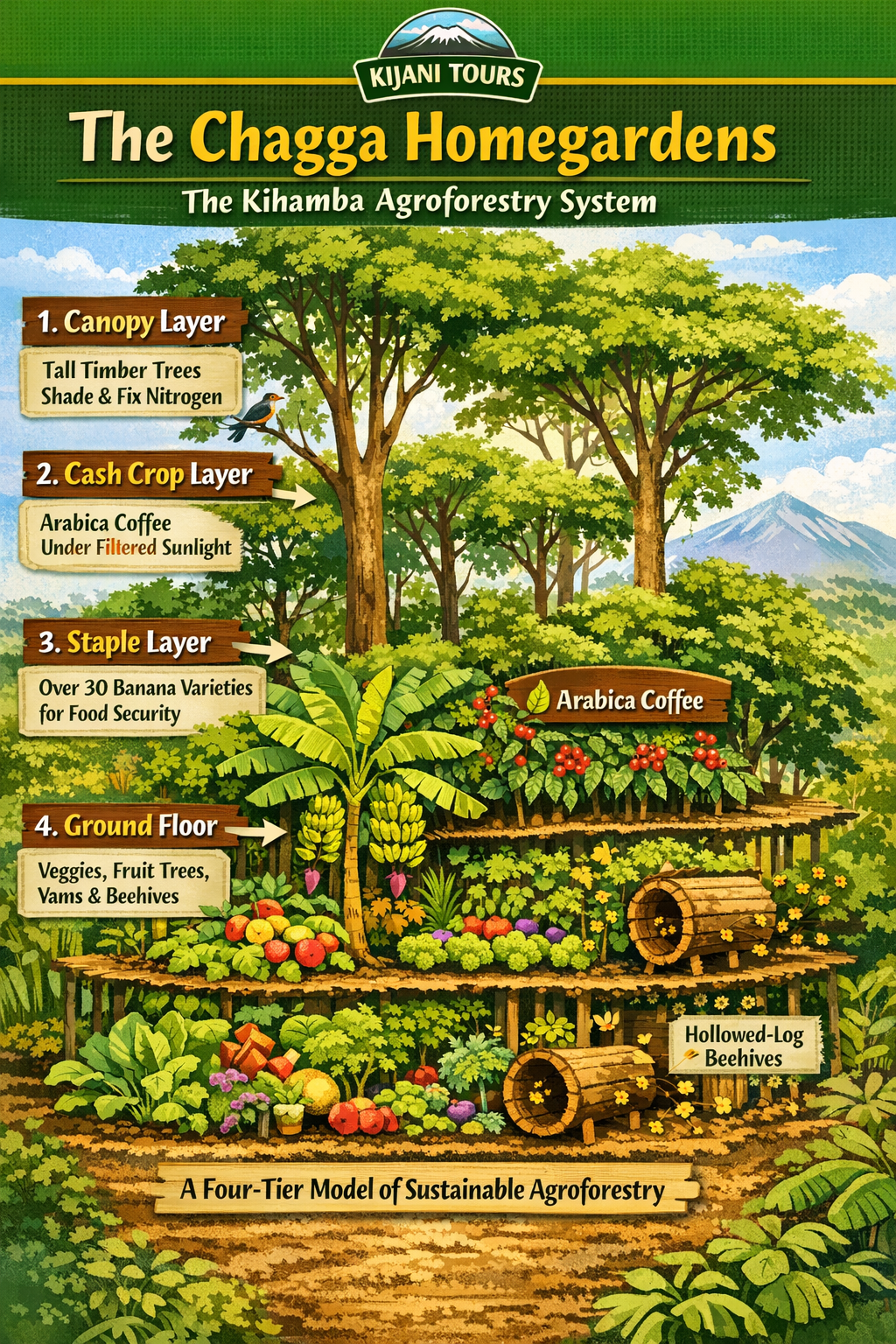

If you want to see a miracle of physics and ecology, you don't look at a skyscraper—you look at a Kihamba. The Kihamba is the traditional Chagga homestead garden. It is a masterpiece of agroforestry that has remained productive for hundreds of years without a single chemical input. While modern agriculture struggles with "sustainability," the Chagga perfected it centuries ago through a four-tiered system:

The Vertical Symphony of the Chagga homestead garden

The High Canopy: Giant timber trees (like Albizia) stretch 30 meters high. They break the force of tropical storms and provide a cooling microclimate that makes the Kihamba up to 5°C cooler than the plains below.

The Mid-Layer: This is where the magic happens. Under the shade of the giants, over 30 varieties of bananas and high-altitude coffee thrive.

The Understory: Shrubs, medicinal plants, and root crops (like yams) fill the gaps.

The Forest Floor: Zero-grazing livestock (cows and goats kept in stalls) provide the manure that fuels the entire system.

This is a closed-loop ecosystem. The livestock eat the banana peelings and tree fodder, and their waste returns nitrogen to the volcanic soil. It is an "umbilical cord" of heritage that proves humans can thrive while enhancing the wild.

3. Isale: The Botanical Boundary of Peace

On the slopes of Kilimanjaro, one plant carries the weight of history: Isale (Dracaena afromontana).

To the Chagga, Isale is not just a plant; it is a legal document, a spiritual seal, and a white flag.

1) The Boundary: It marks the borders of the Kihamba, a living fence that no neighbor would dare cross.

2) The Peace: In moments of deep dispute, a folded Isale leaf is offered as a gesture of reconciliation. Tradition dictates that an offering of Isale cannot be refused.

3) The Anchor: It marks the Kyungu—the spot where the first ancestor of a clan settled.

To understand Isale is to understand how the Chagga have maintained social harmony on a crowded mountain for generations.

4. Kyungu and Kifunyi: Where the Ancestors Sit Among Us

Land in Kilimanjaro is not a commodity; it is a living history. Within the Kihamba, two sites are of ultimate importance: the Kyungu and the Kifunyi.

The Kyungu: The Spiritual Command Center

The Kyungu is the exact spot where the founding father of a clan first stepped onto the mountain soil. It is the spiritual anchor of the lineage. Marked by an ancient tree and the Isale plant, it serves as a "sacred medium." When a family faces hardship—drought, disease, or internal conflict—they return to the Kyungu. Through a ceremony called Mitambiko, they invite the ancestors to sit among them, sharing food and mbege (banana beer) to find clarity and justice.

The Kifunyi: The Sanctuary of the Departed

If the Kyungu is for the living history, the Kifunyi is the sanctuary for the souls who have passed. Historically, this was the site of the "secondary burial," a private grove where ancestors were honored and protected by the forest canopy. It is a place of profound peace, reminding every Chagga that their ancestors remain the guardians of the soil that continues to feed them.

A.) Folklore and Spirituality

Chagga spirituality blends indigenous beliefs with Christianity and Islam. Central to their cosmology is Ruwa, the supreme God associated with the sun and sky. Sacred groves known as Msala and rituals tied to ancestral spirits on Mount Kilimanjaro highlight the community’s deep respect for nature and heritage. The enduring tales of the Wakonyingo further enrich this spiritual tapestry, reminding visitors that Kilimanjaro’s slopes are layered with centuries of myth and meaning.

B.) The Living Traditions of the Chagga

i.)The Intestine Readers: Ancient Foresight

In the Chagga heartland, the slaughter of a goat, sheep, or cow is never merely for meat; it is a sacred inquiry. For centuries, elders—the keepers of mountain wisdom—have practiced the art of Divination through Entrails. After a ritual slaughter, the elders gather in the quiet of the Kihamba. They carefully examine the patterns, colors, and textures of the animal’s intestines. To the untrained eye, it is just nature; to the elder, it is a map.

They "read" these signs to predict seasonal shifts, understand the cause of a family’s misfortune, or seek approval from the ancestors for a new venture. It is a moment where the physical and spiritual worlds intersect, proving that nature holds all the answers if you know how to look.

ii.)The Oil of Grace: The Sheep’s Fat Ritual

On the third day after a burial, a profound ritual of "softening" takes place. The family slaughters a sheep, but the most critical part isn't the feast—it’s the fat (body oil). This oil is gently applied to the grieving family members. In Chagga thought, death is "dry" and "harsh."

The application of the sheep’s fat is a symbolic act of anointing and protection. It is believed to soothe the spiritual friction caused by loss, "cooling" the hearts of the bereaved and signaling to the ancestors that the family is under the clan's care. It is an act of deep, tactile empathy.

iii.) The Shaving Ceremony: A Physical Reset

The third day also brings the Ceremony of Shaving. Family members shave their heads completely, a powerful visual and physical reset.

a) The Symbolism: Hair holds the "old time"—the time of the sickness or the time of the living person. By removing it, the family sheds the weight of the immediate trauma.

b) The New Growth: As the hair begins to grow back, it represents the continuation of the lineage. It is a public declaration that life, like the mountain's forests, always regenerates.

d) Firewood and fodders: The Signal of Return

The final movement in this symphony of grief is the Collection of Firewood and fodders. After the rituals are complete, the family and clan members mark the end of the grief period. This is not just a chore; it is a Ritual of Re-entry. By performing these daily tasks of the Kihamba together, they mark the formal end of the "Deep Grief" period.

It is a communal signal that the "umbilical cord" to the living world has been re-established. The clan members can now return to their daily lives, knowing the ancestor is safely transitioned and the family is once again standing strong.

5. Chagga irrigation canal (Mfongo)

The Mfongo irrigation canals are far more than a feat of hydraulic engineering; they are a living masterclass in community and social governance. Central to this system was the Meku oo Mfongo, the "Guardian of the Water," a respected figure who acted as the mountain’s hydraulic diplomat. The Chagga didn’t just build these channels to move water—they built them to move together, and it was the Meku oo Mfongo who ensured that this life-giving resource reached every homestead with absolute fairness.

The Resilience of the Mfongo Today

Even in 2026, as modern legal procedures and formal water permits become the standard in Tanzania, the Mfongo system endures. Its survival is a testament to its deep integration into the Chagga social fabric. While the government now manages water through formal "Water User Associations" and the Water Resources Management Act of 2009, which requires local water users to participate in sustainable management by obtaining water use permits, adhering to regulations for extraction and discharge (especially for groundwater), preventing pollution, resolving conflicts through Catchment Committees, and contributing data for planning, ensuring equitable access and conservation for present and future needs.

The traditional role of the Meku oo Mfongo often coexists with these new laws. In many villages, the community still looks to their traditional guardians to resolve the daily, local complexities of distribution that a distant legal document cannot always capture. This dual system provides a unique layer of social resilience, keeping the water flowing even when modern infrastructure faces challenges.

Climate Change and the Future of the water

The future of the Mfongo, however, faces a significant shadow: climate change. As the glaciers of Mount Kilimanjaro recede and rainfall patterns become increasingly erratic, the glacial streams that feed these canals are under threat.

The Challenge: Reduced flow during dry seasons and increased "flash floods" during the rains test the hand-dug structural integrity of the canals.

The Adaptation: To protect this heritage, organizations like Kijani Tours and local conservation groups are advocating for a return to the "Guardian" philosophy—combining ancient wisdom with modern Climate-Smart Agriculture. This includes lining key sections of the canals to prevent seepage and integrating them with rainwater harvesting to ensure the kihamba gardens remain lush even as the mountain's "ice cap" disappears.

The Mfongo represents a profound lesson in collective action. It challenges us to reflect: How can we manage our shared global resources with the same integrity and discipline as these ancestral Guardians of the Water? To walk alongside these gravity-defying canals today is to witness a heritage where technical ingenuity, legal evolution, and social harmony flow as one.

5. Blacksmith in the Chagga community

In the shadow of majestic Mount Kilimanjaro, early Chagga society revered the blacksmith as a master artisan and guardian of survival. Using ingenious techniques—fanning roaring charcoal fires with goatskin bellows, hammering glowing iron on ironstone anvils, and gripping it with long pincers—they forged tough hand hoes for banana groves, razor-sharp spears, swords, and arrowheads for warriors, plus ceremonial items.

Long before modern trade routes reached the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, the Chagga people relied on an essential partnership with their neighbors, the Pare. The Pare and Taita tribes were well-known for their iron smelting, supplying the Chagga with raw and semi-processed iron instead of finished tools. From this material, Chagga blacksmiths took charge. This iron was then forged by Chagga blacksmiths into tools and weapons, supporting their agricultural and military needs. This relationship allowed the Chagga to maintain control over craftsmanship while benefiting from the Pare’s expertise in metallurgy.

In the 19th century, as competition and rivalries among Chagga chiefdoms grew stronger, the demand for iron increased sharply. Weapons needed to be tougher, and farming tools had to be more effective. Iron sourced from the Pare became a crucial resource that fueled both political power and agricultural productivity.

This exchange reveals an important truth: the Chagga's strength came not from importing ready-made goods but from transforming iron obtained from the Pare into tools for survival, resilience, and authority on the slopes of Kilimanjaro.

Today, this thrilling legacy endures, drawing adventurous travelers on cultural tours near villages like the Nkini clan in the Mae chiefdom (Siha district), which was particularly respected for its metalworking traditions, Mamba, and Marangu, to watch local blacksmiths at work—sparks flying as they forge tools and spearheads, echoing their ancestors' daring spirit.

6. Rites of Passage: From Maseka to Mangati

Deeply rooted in the volcanic soil of Kilimanjaro, the social structure of the Chagga people was historically governed by Rikas, or generation groups, which ensured that every individual played a vital role in the community’s harmony. The journey from childhood to adulthood was far from a simple milestone; it was a rigorous, sacred process of instruction designed to forge the next generation of leaders and stewards. Young men underwent Ngasi (Male Initiation), where they resided deep within the mountain forests to master the secrets of manhood, the art of hunting, and the strategic weight of tribal defense.

Simultaneously, young women participated in Shija (Female Initiation), a months-long immersion within the shelter of the ancestral banana groves, where they were instructed in sacred rituals, the responsibilities of motherhood, and the intricate social fabric of the clan. While the formal ceremonies of the Ngasi and Shija largely transitioned during the colonial era, the core spirit of these rites remains a cornerstone of cultural tourism in Moshi and the wider Kilimanjaro region today. The values they instilled—unwavering respect for elders, deep communal responsibility, and a fierce protection of the land—continue to define the modern Chagga identity, proving that even as traditions evolve, the "umbilical cord" to their ancestral heritage remains unbroken and continues to guide the path of the Chagga communities.

7. The Sacred Sip: Mbege and the Heart of Chagga Hospitality

To step into a Chagga home on the slopes of Kilimanjaro is to be greeted by more than just words; you are greeted by Mbege. This traditional beer, meticulously brewed from fermented bananas and finger millet, serves as the ultimate cultural signature of the mountain. Far more than a mere beverage, Mbege is the social glue that has held the community together for centuries.

In the Chagga heartland, every sip carries a deeper meaning. It is the sacred bond shared at weddings to unite two lineages, the solemn offering at funerals to honor those who have passed, and the peace-making nectar poured during communal gatherings to resolve disputes. To accept a gourd of Mbege is to participate in an ancient ritual of unity—an invitation to connect with a spirit of hospitality that has sustained this community for generations.

8. Medicinal plants in Chagga people

The Green Cathedral: Walking Through Kilimanjaro’s Ancient Pharmacy

Beyond the spicy, sharp scent of the Ikiingiyi (Ginger Bush), the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro hold a deeper secret. To the untrained eye, the tangled greenery of a Chagga Kihamba garden or the mist-veiled mountain forest is "nature." But to the Chagga, it is a living, breathing cathedral of healing—a "Green Pharmacy" where every leaf carries a name and every root holds a story.

For generations, the Chagga have been quiet masters of the mountain’s biodiversity. Their wisdom isn’t stored in dusty archives, but in the hands of elders and the soil of their ancestral gardens.

Here are the silent healers that have stood guard over the community’s health for centuries:

The Msesewe: The Bitter Anchor (Rauvolfia caffra)

Commonly known as the Quinine Tree, the Msesewe is perhaps the most spiritually significant tree on the mountain. If you’ve ever tasted Mbege (traditional banana beer), you’ve met the Msesewe—it is the bitter bark of this tree that stabilizes the brew. The Healing: Beyond the gourd, a decoction of its bark has been used for centuries as a potent remedy for malaria and pneumonia.

The Spirit: You will often find the Msesewe leaning over a Mfongo canal. It is the mountain’s hydraulic diplomat, acting as both a structural and spiritual anchor for the water that feeds the homesteads.

The Mseni: Breath of the Mountain (Olea europaea ssp. cuspidata)

The African Wild Olive is a symbol of sheer endurance. While its wood is legendary for its strength, its true gift lies in its ability to help the community breathe.

The Wisdom: In the thin, crisp air of the high altitudes, the Chagga use infusions of its leaves and bark to soothe respiratory struggles and balance high blood pressure. It is a gentle, enduring remedy, mirroring the resilience of the tree itself.

The Mkonde-konde: The Ancient Giant (Prunus africana)

The Red Stinkwood is a global celebrity in modern medicine today, but the Chagga recognized its power long before Western journals documented it.

The Remedy: This tree is a protected treasure. Traditionally, its bark is pounded and boiled to treat internal inflammation and urinary health. Its presence on the mountain is a testament to an advanced botanical science that has thrived here for centuries, independent of the outside world.

Mvunja-kongwa: The Bone-Setter (Synadenium glaucescens)

Often found standing guard near the entrance of a homestead, this succulent-like tree is a physical and spiritual protector.

The Ritual: Its name translates to "the breaker of the yoke," a powerful nod to its ability to break the hold of injury. The milky latex and roots are carefully prepared by elders to treat deep wounds and set broken bones. It is the "emergency room" of the forest, a bridge between physical repair and ancestral grace.

The Vumbasi: The Scent of Home (Ocimum gratissimum)

If you want to know the scent of a Chagga childhood, you look to the understory of the garden. Vumbasi, or Wild Basil, is the ever-present "first aid" plant found in every Kihamba.

The Use: Its aromatic leaves are a comforting remedy for everything from a restless stomach to a heavy chest cold. Whether inhaled as a fragrant steam or crushed for a quick infusion, Vumbasi is the humble, ever-present healer that is always within arm’s reach.

The Healing Cord: Preserving Faint Echoes

To walk through the mountain mists with a Kijani Tours guide is to realize that the forest is not a commodity—it is a conversation. However, as rainfall patterns shift and the "Iron Snake" of urbanization reaches higher, this ancient pharmacopoeia faces a quiet threat.

By stepping into these gardens with us, you aren't just observing a tradition; you are helping to keep it alive. We document these plants and share their stories not to freeze them in time, but to ensure that the Chagga Green Pharmacy remains a vibrant, healing legacy for the generations yet to come.

9. Political Evolution of the Chagga

The journeys from ancient chiefdoms to Africa’s most successful cooperatives are a masterclass in adaptation. While the Kihamba is the backbone of the family, the Mangi system was the backbone of the nation. For centuries, the Chagga were organized into 37 autonomous chiefdoms, each led by a Mangi (Chief). These weren't just figureheads; a Mangi held ultimate authority over land distribution, the management of the Mfongo water canals, and clan justice.

The Age of the Mangis

In the 19th century, legendary leaders like Sina of Kibosho and Marealle of Marangu turned their chiefdoms into regional powerhouses. They were master diplomats and warriors, utilizing the Ngasi age-set system to train young men in defense and communal labor. This era was a delicate balance of spiritual authority and agricultural stewardship.

Mangi Meli: A Chief against the Empire

When German colonial forces pushed into East Africa in the late 1800s, they met a fierce obstacle in Mangi Meli of Moshi. Born in 1866, Meli became ruler in 1891 and immediately became a symbol of resistance.

a) The Rare Victory: In 1892, his forces defeated the Germans at the Battle of Moshi, forcing a retreat that lasted for weeks.

b) The Ultimate Sacrifice: Eventually betrayed and captured, Meli was executed in 1900 at a site in Old Moshi. In a final act of colonial cruelty, his head was severed and sent to Germany. Even today, his spirit looms large as his descendants continue the search for his remains to bring their king home for a dignified burial.

Introduction of Christianity In Kilimanjaro

Exploring the lush foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro with Kijani Tours reveals a living history that stretches far beyond the summit. This spiritual journey began in 1848 with missionary Johannes Rebmann’s first sighting of the snow-capped peak, sparking a transformative era where the "Cross and Flag" moved onto the mountain's fertile slopes. The Catholic Spiritans, arriving in 1868, left an incredible architectural legacy, most notably the 1893 Kibosho Church—a massive, Bavarian-style stone masterpiece that became a vital center for early healthcare and civic life. Meanwhile, the Lutheran Leipzig Mission profoundly shaped the region's intellect by championing education and literacy in the mother tongue, translating faith into the local Kichagga language in hubs like Marangu and Machame. These dual influences helped the Chagga people navigate the colonial era, establishing the communities around Moshi as some of the most educated in Tanzania.

Beyond the historic steeples, this era introduced the "black gold" of Arabica coffee, a missionary garden experiment that blossomed into a global industry and redefined the Chagga economy. On a Kijani Tours cultural excursion, you will stroll through ancestral "Kihamba" gardens where these coffee traditions continue to thrive alongside the ancient reverence for the high god, Ruwa. This unique blend of devout Lutheran and Catholic practices, seamlessly woven into ancestral respect, creates a spiritual tapestry unlike any other. By going behind the scenes with our expert guides, you don’t just see the peaks—you connect with the resilient spirit, legendary heritage, and vibrant culture of the people who call the slopes of Kilimanjaro home.

How Missionary Schools Shaped Kilimanjaro’s Legacy of Learning

When you think of Kilimanjaro, the first image that comes to mind is probably the snow-capped peak rising above the plains of Tanzania. But beyond its breathtaking scenery, the region also carries a fascinating story about education—one that began in the late 19th century with the arrival of missionaries.

The Lutheran Beginnings

In 1893, the Leipzig Lutheran Mission made its way to Machame, picking up where the Church Missionary Society had left off before being shut down by German colonial authorities. By October of that year, they had planted their first mission station, and just a year later, in 1894, a formal school opened its doors. This was the spark that lit a chain reaction: more schools followed in places like Mamba (1902), Kidia, and Old Moshi.

The Catholic Expansion

Around the same time, Catholic missionaries—the Holy Ghost Fathers (Spiritans)—were making their way inland from the coast. Led by Bishop Jean Marie de Courmont and Father Alexander Le Roy, they reached Kilimanjaro in 1890 and established one of their most influential missions at Kilema. Unlike many schools of the era, their approach went beyond religious and academic lessons. They taught practical skills too, especially in agriculture. In fact, they were the ones who introduced Arabica coffee to the region—a crop that would go on to become a cornerstone of Kilimanjaro’s economy and identity.

A Region Transformed

By the early 20th century, the educational footprint of these missions was undeniable. The Spiritans built an extensive network of schools, and by 1934, they were running more than 200 primary schools with over 14,000 students enrolled. These efforts didn’t just provide literacy and religious instruction—they reshaped the social fabric of Kilimanjaro, turning it into one of the most educated regions in Tanganyika.

The Legacy Today

The seeds planted by those early missionaries continue to bear fruit. Kilimanjaro’s reputation for valuing education is deeply rooted in this history, and the introduction of coffee farming remains one of the most enduring legacies of its vocational training. What started as small mission stations more than a century ago has grown into a culture of learning and innovation that still defines the region today.

The Coffee Connection: From Mission Gardens to a Global Stage

The story of Kilimanjaro’s world-famous coffee began in the 1890s with the arrival of German Spiritan missionaries at the Kilema Mission. Tucked away in their luggage were Arabica coffee seeds from Reunion Island—a small gift that would forever alter the landscape of the Moshi region. Recognizing that the mountain’s mineral-rich volcanic soil and cool, high altitudes provided the perfect cradle for cultivation, the missionaries established their first crops. Soon, they began sharing these seedlings and specialized farming techniques with the local Chagga community, sparking a profound cultural and economic evolution.

The "Iron Snake" and the Great Coffee Boom

While the mission gardens proved the crop could thrive, it was the arrival of the Usambara Railway—locally known as the "Iron Snake"—that truly unlocked the mountain’s potential. To understand how Kilimanjaro transformed from a collection of ancient chiefdoms into a global gateway, we must examine the moment when the mountain intersected with the industrial age. While the Mangi chiefs navigated the arrival of colonial powers, this massive project of steam and steel was quietly carving its way through the volcanic landscape.

Before the tracks were laid, transporting goods to the coast was a grueling, weeks-long trek on foot. Introduced under German rule, the Usambara Railway was a 350-kilometer engineering marvel designed to bridge the fertile slopes of Kilimanjaro with the salt-sprayed Indian Ocean Port of Tanga. Construction began in 1893, and by 1912, the first locomotive hissed its way into Moshi, cementing the town’s status as a regional powerhouse and the commercial heartbeat of East Africa.

The Industrial Birth of Modern Moshi

The "German Era" of Neu-Moschi (New Moshi) brought far more than a change in architecture; it forged a permanent, direct heartbeat between the fertile slopes of Kilimanjaro and the global stage. Before the railway arrived, the mountain’s bounty was isolated by geography. But with the hiss of the first locomotive, the premium Arabica beans meticulously nurtured in traditional Chagga Kihamba home gardens suddenly gained a "fast-track" line to the demanding markets of Europe.

This newfound access triggered a wave of transformation that still defines the region’s identity today. A tangible, enduring reminder of this era is the German administrative building, which once served as the nerve center for this burgeoning trade. Remarkably, this sturdy structure still stands in Moshi today, serving as a living landmark of the town's industrial birth.

As Moshi shed its skin as a quiet military outpost, it rapidly evolved into a bustling administrative and trade center. Walking past these historic walls today, you can still feel the momentum of those early coffee shipments—the very foundation of the vibrant, modern trade culture that greets travelers in Moshi today. It remains a point of great communal pride, cementing a history where high-altitude coffee and international connection first met.

A Shifting Social Fabric: The demand for labor and the allure of a growing trade economy drew people from across the region. These new migration patterns reshaped the social dynamics of the mountain, creating a rich cultural melting pot and diverse industrial landscape.

The Foundation of Economic Independence: This era of direct trade did more than just move beans; it instilled a spirit of organization. This collective strength eventually laid the groundwork for the Kilimanjaro Native Cooperative Union (KNCU)—Africa’s first-ever African-run coffee cooperative.

By turning local harvests into a world-renowned commodity, the railway and the mission seeds ensured that Moshi would be more than just a dot on a map. It became a premier global heartbeat for high-altitude coffee, preserving a rich agricultural heritage that remains the pride of the Chagga people.

The Rise of the Cooperatives

After the dust of World War I settled, and the era of military resistance faded, a new kind of revolution began to stir on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. It was a revolution not of spears, but of strategy and collective strength. Have you ever wondered how the Chagga people became some of the most economically resilient communities in Africa? The answer lies in a pivotal shift that occurred in the 1930s.

Driven by visionaries like Joseph Merinyo and Charles Dundas, a movement was born that would change the mountain’s history forever: the Kilimanjaro Native Cooperative Union (KNCU). This wasn’t just an organization; it was a defiant declaration of independence. As Africa’s very first African-run coffee cooperative, the KNCU achieved something revolutionary—it reclaimed the power from colonial middlemen and placed it directly back into the weathered, capable hands of the Kihamba farmers.

By organizing themselves, these coffee growers ensured that the rewards of their volcanic soil stayed within their own communities. This legacy of the "cooperative spirit" is the secret behind the modern-day prosperity you see in Moshi today. It is a story of how the Chagga transitioned from defending their land to mastering the global markets, proving that true resilience grows from the roots up.

The Coffee Connection: From Garden to Global Market

In the 1890s, German Spiritan missionaries introduced Arabica coffee to the Moshi region by planting seeds from Reunion Island at the Kilema Mission. They leveraged Kilimanjaro’s fertile volcanic soil and high altitude to establish the crop, eventually sharing seedlings and farming techniques with the local Chagga community.

This transition from mission gardens to local farms laid the foundation for Moshi’s status as a premier global coffee hub. For the Chagga people, this railway was transformative. Before the tracks arrived, transporting goods meant long, arduous journeys on foot. With the arrival of the "Iron Snake," the high-altitude coffee grown in the kihamba home gardens suddenly had a "fast track" to international buyers in Europe. This access changed everything:

a) Urbanization: Moshi evolved rapidly from a military outpost into a bustling commercial hub for trade and administration.

b) Social Shifts: The demand for labor and trade drew people from across the region, creating new migration patterns that reshaped the social fabric of the mountain.

c) Economic Foundation: This era of direct trade laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Africa’s first African-run coffee cooperative, the KNCU.

A Legacy You Can Still Visit

Today, the railway stationsremains a stark reminder of how the Chagga adapted to foreign infrastructure to fuel their own prosperity. When you walk through Moshi with Kijani Tours, the old railway station and the surviving colonial buildings serve as tangible links to this pivotal era—a time when the mountain’s agricultural wealth first met the global stage.

Modern-day Democracy

When Tanzania gained independence in 1961, the chiefdom system was formally abolished. Figures like Thomas Marealle and Solomon Eliufoo transitioned the Chagga from clan governance to National politics.

11. What You Take Home after visiting Chagga villages

a) A Blueprint for Sustainable Living

In a world obsessed with "new" technology, the Chagga Homestead (kihamba) is a humbling reminder that the most effective solutions are often ancient. You take home the realization that high-production farming doesn't require chemicals or destruction. By observing the four-tiered agroforestry system, you see a "Zero-Waste" harmony where every fallen leaf and every livestock animal play a role in a perfect, closed-loop cycle. You learn that we don't have to conquer nature to thrive; we simply have to listen to it.

b) The Power of Sacred Boundaries

The Isale plant teaches us a profound lesson about conflict and peace. In our fast-paced modern lives, we often forget the art of reconciliation. Visitors leave with a deep respect for the "Isale Philosophy"—the idea that a single gesture of peace can stop a war, and that boundaries are not just fences, but sacred commitments to our neighbors. You learn that social harmony is just as important as ecological health.

c) The Strength of the "Umbilical Cord."

Visiting the Kyungu and Kifunyi forces a moment of self-reflection: Where are my roots? In the West, we often view land as a commodity—something to be bought and sold. The Chagga teach us that land is a "living history." You take home a renewed desire to connect with your own ancestry and a realization that we are merely temporary guardians of the soil for those who will come after us.

Kilimanjaro’s Whisper: A Call to Reflect

As you sit in the quiet of the homestead, sipping on a cup of freshly roasted coffee or a gourd of mbege, the mountain seems to ask a silent question:

"Are you a consumer of the earth, or a steward of it?"

The Chagga don't just live on Kilimanjaro; they live with it. They have mastered the art of "Vertical Living," where growth is measured not just in height, but in the depth of one's roots. You leave the Chagga Homestead (kihamba) feeling refreshed, not just by the mountain air, but by the clarity of a culture that knows exactly who it is. You realize that "progress" doesn't always mean moving forward—sometimes, it means returning to the wisdom of the trees.

Conclusion: Beyond the Summit, Into the Soul

A journey to the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro is often measured by the height of the peak, but the true depth of the mountain is found in the Chagga heartland. Here, culture isn’t a relic stored in a museum; it is a living, breathing pulse found in the daily tending of a Kihamba garden, the shared gourd of Mbege, and the quiet rustle of an Isale leaf marking a boundary of peace. It is a world where ancient engineering—like the gravity-defying Mfongo canals—coexists with modern water laws, and where the cooperative spirit of the KNCU continues a legacy of independence that began long before the first rail was laid.

As you walk through these mist-shrouded groves with Kijani Tours, you begin to see that the Chagga have not merely survived on this mountain; they have flourished by listening to it. From the legendary shadows of the Wakonyingo to the resilient innovations of modern-day farmers, this community reminds us that "progress" does not require the destruction of the past. Instead, it is an ever-evolving "umbilical cord" of heritage that adapts, grows, and sustains.

We leave these villages not as conquerors of a peak, but as guests of the guardians. We take home more than photos; we carry a newfound humility and a question that lingers long after the mountain fades from view: "Are you a consumer of the earth, or a steward of it?" The Chagga have already given us their answer through centuries of harmony. Now, as you step back into your own story, you carry a piece of theirs—a legacy of resilience, respect, and the enduring wisdom of the trees.

Adventure That Gives Back: Your Tanzanian Journey with Kijani Tours

Before dawn on Mount Kilimanjaro, every step toward Uhuru Peak is a test of will against thin alpine air. You move through five distinct ecosystems—rainforest, moorland, alpine desert, and arctic summit—until sunrise spills over Africa’s highest point. The climb demands resilience, but it offers something rare in return: clarity, strength, and a deep connection to the land. Days later, the stillness of the summit gives way to the sweeping plains of the...

A silver mist drifts through Lemosho’s mahogany glades, carrying the scent of damp earth and ferns. Your trekking poles press into the soft trail, each step intentional, each breath a conversation with the mountain. Unlike the rush of younger climbers chasing Kilimanjaro’s summit, this is a slow-paced climb designed for senior adventurers. At Kijani Tours, we believe a senior-friendly ascent is about seeing, feeling, and connecting. Our guides move with care, watching...

Share This Post